The Calories In Calories Out (CICO) theory explains weight management from the perspective of energy balance, and essentially states that one’s change in weight is a property of how much you are eating and how much activity you are performing. In other words, assuming a normal activity level, if you are losing weight, then you are eating a low amount of calories, if you are gaining weight, then you are overeating, and if your weight is stable, then you are eating the right amount.

Belief in the CICO theory is widespread throughout the general public. Thus, it might be very surprising to hear from your Functional Medicine provider that you may be potentially undereating. “But I don’t understand… how can I be undereating if I am not losing weight?” However, despite this common belief, the CICO theory is actually not true. The flaw of the theory is that it assumes that the resting metabolic rate is static (does not change), when in fact, the resting metabolic rate may go down in the context of various types of metabolic dysfunction.

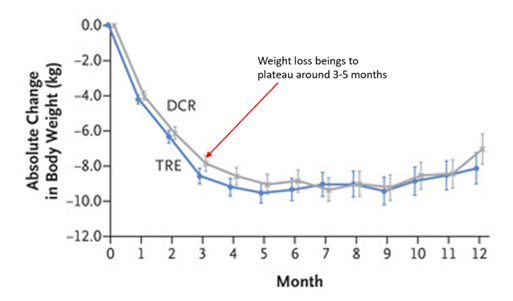

Anyone who has ever tried to intentionally lose weight will affirm that this is the case. For example, consider someone who at baseline is maintaining their weight at 2000 Calories per day. They then decide they would like to lose some weight, so they decrease the caloric intake to 1500 Calories per day. At first, they will lose approximately 1 pound per week. This continues for some time, however, at some point, despite no changes in intake or activity/exercise levels, the weight loss slows down and ultimately plateaus. Why? Because your body gets used to the caloric restriction. It is actually an adaptive mechanism to deal with a pseudo-starvation state. In the context of a pseudo-starvation state, your body is incentivized to lower the metabolic rate in order to preserve the mass of the organism. Otherwise in nature, you would continuously lose weight until ultimately you would die. The lowering of the metabolic rate in response to chronically low caloric intake allows a person in the starvation state to survive for longer. In our practice, we see this all the time, patients may be consuming as little as 700-800 Calories per day and are still not losing weight. If the CICO theory were true, this would be impossible.

Figure 1. Change in weight from baseline over time in response to caloric restriction. Note how weight loss begins to plateau after three to five months despite relatively constant calorie intake and exercise. Adapted with permission.1

Often times, unintentional caloric restriction may not be perceived. “But I do not feel like I am undereating. I eat three meals a day, I feel satisfied and full when I am done, and I just can’t imagine eating more food.” Sometimes, our perception around how much food we should be eating is thrown off by issues around appetite. Many people have poor appetite, meaning that even though they are objectively undereating, they inappropriately do not feel hungry. From a functional perspective, this can happen due to overconsumption of low caloric density foods (e.g., salad), stress, and gastrointestinal dysfunction (e.g., poor digestion, chronic nausea, etc.).

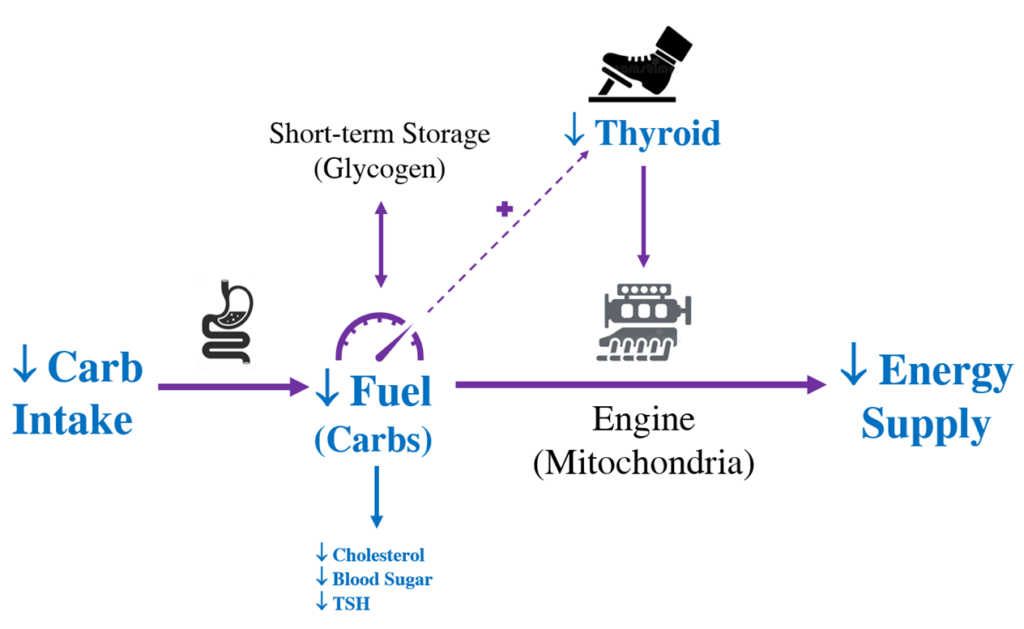

In our bioenergetic model, we use the term “fuel deficiency” to describe what is happening. For example, in order for a car to move, the first step is that gasoline must go into the tank. The car requires fuel for the engine to burn in order to ultimately produce the energy that turns the wheels. Chronic caloric restrictions leads to fuel deficiency, which is the state of “running on empty” and ultimately leads to stress activation, secondary hypothyroidism, and ultimately a reduction in the metabolic rate.

Figure 2. Caloric restriction causes fuel deficiency, low energy supply, stress activation, and ultimately a reduction in the metabolic rate.

Similarly, overtraining produces the same effect. For example, consider the same patient above, but instead of decreasing the caloric intake from 2000 Calories to 1500 Calories per day, they keep the caloric intake the same, but add an extra 500 Calories per day of exercise. In this situation, the same thing happens, weight loss occurs in the beginning, but plateaus over time due to the relative fuel deficiency and lowering of the basal metabolic rate. The condition in which the exercise dose is too high resulting in over-activation of the stress system and metabolic dysfunction is called “overtraining.” If you are an athlete who is experiencing fatigue, insomnia, hair loss, anxiety, or hormone imbalance, you may be overtraining.

The idea of fuel deficiency can be difficult to grasp. Many health influencers on social media proport long-term health benefits of caloric restriction and intermittent fasting. Additionally, with many people concerned about potential weight gain, subconscious belief in the CICO theory may lead people to chronically undereat to prevent obesity. But when we understand the idea of fuel deficiency-induced metabolic dysfunction, we realize that this is not a good long-term strategy. We want patients to live a high energy life, which is a lifestyle that involves eating a lot and burning a lot. The goal is to optimize the energy supply. When we have this mindset, we will have a strong metabolism, and this is actually what will prevent obesity and lead to optimal health in the long-term.

If you are interested in learning about the concept of fuel deficiency in more detail, including analysis of the underlying scientific literature that supports this idea, consider reading Chapter 1 in our manual.

References:

- Liu D, Huang Y, Huang C, et al. Calorie restriction with or without time-restricted eating in weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(16):1495-1504. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2114833